© cdn.fusion.net

In arguably the arrest of the century, on Saturday, February 22nd Mexican authorities captured Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman in the coastal city of Mazatlana. As the head of the Sinaloa cartel, Guzman’s actions made the exploits of other famous mobsters pale in comparison. He made more money every month than the total net-worth of John Gotti, his operations ran through more continents than Al Capone’s syndicate did countries, and by the time Pablo Escobar would have been El Chapo’s age he was already dead for fifteen years. In the past few days’ news of the fallen drug lord made international headlines. The vast majority of media outlets hailed his capture as a major victory for the war on drugs. However, news readers and viewers are fed selective information about the details and “importance” of his capture that are designed to achieve a constructed outcome. Beneath the cinematic images of El Chapo in handcuffs lies a darker truth: his arrest represents a failure in drug policy rather than a triumph. This article intends to explain how Guzman’s capture is a potemkin victory masking how current drug policies are actually fueling violence, strengthening criminal organizations, raising narcotic purity levels, and bottoming drug prices. Understanding how the arrest of a kingpin like El Chapo increases rather than reduces drug-related crime requires some knowledge about the general impact of prohibition policies on illicit drug economies as well as information about the specific effects of recent Mexican drug policies on organized crime. When these variables are considered, the capture of the world’s largest drug lord reflects the shortfalls in drug policy rather than their triumph.

Prohibition on Illicit Drug Economies: a Cyclical Problem

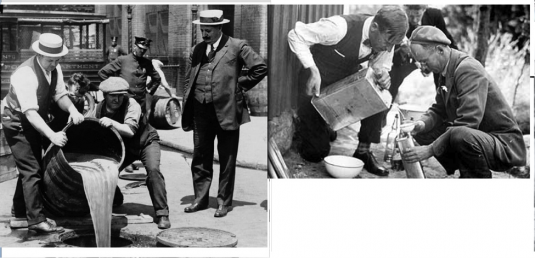

Drug prohibition was designed to lower drug consumption by using force to raise the costs of production, transportation, and sales for growers, transporters, and dealers. In theory, state coercion drives down production and availability, drives up prices of narcotics, and subsequently discourages consumers from buying and using drugs (Bertram & Sharpe, 1997, p.43). Inadvertently, however, the drug war creates a black market. Narcotics remain cheap and easy to produce but they become far more expensive for consumers to purchase, which results in spectacular profits for distributers (Bertram & Sharpe, 1997, p.43). The artificially high profits create a paradoxical effect for drug policy by providing incentives for drug suppliers to remain in the trade and for new recruits to enter. While intending to discourage black markets, law enforcement ultimately produces a “carrot” (i.e. massive profits) that provides incentive to sustain and perpetuate black market affairs (Bertram & Sharpe, 1997, p.46). This contradictory outcome clearly undermines the rationale behind prohibition. As prices rise, profits rise, more suppliers enter the market and prices are driven back down (Campos, 2011, p.15). The profit-supplier dynamic accounts for the anomaly that prices of major illicit drugs have either dropped or remained relatively steady over the past two decades despite massive state expenditures on supply reduction.

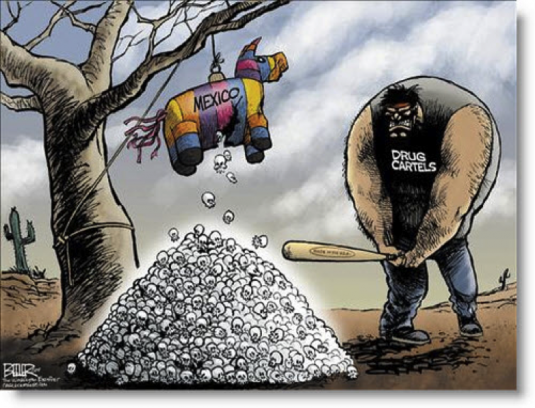

Coupled with the “profit paradox”, drug prohibition directly and indirectly produces more crime and violence. Directly, imprisonments and murders of cartel members, particularly high ranking ones such as El Chapo, create “power vacuums” that promote internal violence within organizations and violence across organizations struggling to re-establish trading networks (Friman, 2009, p.286; Snyder & Martinez, 2009, p. 266; Bertram & Sharpe, 1997, p.47). The drug trade does not depend on any one actor for success because consumers drive the industry. Removing one (or several) members of a cartel may be great publicity for law enforcement but in reality, these characters are simply replaced, and often by even more barbaric individuals (Snyder & Duran-Martinez, 2009, p.266; Friman, 2009, p.286). For example, four days after the death of Heriberto Lazcano (a notoriously vicious leader of the Los Zetas cartel) in a shootout, a news article identified the following replacement process, “With the death of Lazcano, the Zetas are now run by a ruthless leader, Miguel Angel Trevino Morales, [a man who] has a reputation for being even more brutal than Lazcano” (Al Jazera, October 11, 2012). In policy terms, arresting or murdering cartel members is perhaps akin to cutting off the head of a Hydra – two more heads grow to replace the loss.

Indirectly, state prohibition against drug organizations necessitates the use of violence by the narcotic organizations. Illicit goods markets operate without the legal securities against fraud and violence offered by the court system. Instead of facilitating industry through subsidies and tax incentives, the state aims to disrupt illicit networks. In the absence of state-sanctioned resolution and enforcement mechanisms, violence serves as a selective tool for “illicit market regulation” (Friman, 2009, p.286). In effect, the violence found in illicit economies ebbs and flows according to the needs for security that remain sensitive to various environmental pressures such as the legal environment, competition, and internal organizational disputes. These dynamics explain why drug related violence can vary widely across time in the same place, or vary widely across places at the same time.

Depending on how market pressures manifest, the need for violence may reach a threshold that current structural constraints cannot satisfy, and then organizational adaption ensues. For example, traditionally in Mexico cartel enforcement was informal and delegated to family friends and neighbours when there was a need for violence. The informal method of enforcement was facilitated by deep and extensive relations with corrupted politicians and police. When the security relationships between Mexican cartels and government agents altered due to democratization reforms in the 1990’s, the need for violence increased beyond the capabilities of family based social networks, and enforcement privatization resulted. The Gulf Cartels formation of the Los Zetas (1997) from defecting elite airborne Special Forces units illustrates the privatization that swept through Mexican cartels in the 1990’s and early 2000’s. By 2006, the privatized enforcement evolution among cartels was fully entrenched with two in three cartel members having a military background. As the Mexican experience explains, criminal organizations adapt and evolve according to the pressures exerted on them. The greater the legal pressure applied on illicit economies, the greater the need for violence.

In illicit markets we see that prohibition inflates commodity prices and this in turn creates incentives for individuals to remain in the business and for new ones to enter. The competition among black market actors stabilizes prices and purity levels over the long term, and this explains why increasingly expensive anti-narcotic policies have been met with rising drug purity rates and similar if not cheaper consumer drug prices. Moreover, the process by which prohibition is realized directly and indirectly produces the violence that the policies are meant to solve. Well intentioned prohibition policies create a cyclical process where a “self-reinforcing violent equilibrium” emerges: incremental increases in violence by cartels raise the incentives of the government to « prosecute traffickers » which advances additional confrontations with traffickers when, « as a result of the detention of drug lords », the remnants of the fragmented criminal organizations fight each other in successive battles (Rios, 2013, p.139). Consequently, the arrest or capture of a criminal such as El Chapo is ultimately futile because the policing framework perpetually creates the socio-economic environment for future criminals: drug consumers persist, narcotics remain cheap to produce and expensive to sell, and the violence calculus embedded within illicit economies ensures that fortune favours the ruthless.

Mexican Drug Policy: Empowering the Beast

For the big picture view of El Chapo’s arrest on the Sinaloa cartel, it is also important to understand the specific impacts that Mexican drug policy had on the organizational designs of cartels. Prior to launching the drug war, Mexican Policy makers looked to Columbia’s drug enforcement strategy in the 1980’s and found that the targeting of drug lords splintered criminal organizations, and drug related violence decreased as the Columbian Cartels diffused into smaller groups. Drawing on Columbia’s experience, Mexican authorities employed similar tactics in 2006 as part of their « kingpin strategy » in the drug war. The kingpin strategy aimed to dismantle cartels and induce fragmentation by targeting leaders, and high ranking members of criminal organizations. On this mark, Mexico’s strategy has been extremely successful. As the Columbian experience predicted, Mexican enforcement successes induced cartel fragmentation and increased the number of cartels operating in Mexico. From 2006 to 2011, the number of cartels exploded from six to sixteen. However, the unforeseen and unintentional consequence of these expanding numbers was that certain cartels, such as the Sinaloa organization, not only adjusted but thrived becoming more invulnerable to future law enforcement “successes”.

Specifically, by 2006, the private cartel enforcement wings had grown in strength and power. The growing strength of private armies stemmed from the fact that cartels used them for enforcement and drug trafficking. After the shock instigated by the Mexican Drug War, the enforcement wings fragmented and broke away from their former cartels. For example, the Beltran-Leyva enforcement wing violently separated from the Sinaloa cartel following the arrests of an important member in 20081. Learning from the fallout caused by empowering enforcement wings through their dual use in carrying out violence and drug trafficking roles, cartels corrected the mistake by adopting two-tiered organization models that could balance and constrain enforcement wings within cellular network systems. Two-tiered networks are typified by decentralized, cell-based « enforcement » periphery members operating around a logistical core. Particularly influenced by the paramilitary framework of the Los Zetas, the two-tiered network model became the practical framework for criminal organizations because it balances the dual-need of secretive logistic transport operations with increasingly necessary public expressions of power.

Clues of this organizational design existing in the Sinaloa cartel were revealed with the arrest and confession of Jesús Israel de la Cruz López. Known as “El Tomate”, Cruz López disclosed that the Sinaloa structure has changed in response to the cartel fragmentation with the Beltran Leyva organization. El Tomate operated as a middle-node connection between an enforcement cell unit and higher ranking members of the organization. His confession sheds insight into the workings of the cellular enforcement network, and he explains: « Guzmán and Zambada prefer to have many cells leaders instead of allowing one person to have a majority of the power in a single territory » (Bugs, January 12 2011). From the Beltran Leyva split, the Sinaloa cartel learned that non-cellular enforcement wings allowed individuals to procure status and as they climbed through the ranks they « soon became [Sinaloa’s] enemies with mafias of their own » (Bugs, January 12 2011). By delegating enforcement to cellular units, cartels such as the Sinaloa organization are now able to express their power while simultaneously making it difficult for authorities to utilize the captures of periphery members to arrest members of the logistical core. The network design also allows for members of the logistical core to be captured without dismantling the entire organization. As a result, experts have noted that the Sinaloa cartel remains virtually « unaffected by high-level government arrests », and retains the ability to traffic drugs (Molzahn et all, 2012, p.29). In practical terms, the Mexican drug war made criminal organizations more resilient, durable, and cohesive which reduces the impact of law enforcement successes on cartel functioning.

The Lesson: Players Change but the Game Remains

A picture of a shackled El Chapo begins this article. As the saying goes, a picture may be worth a thousand words, but in this instance, a thousand plus words are necessary to truly grasp the complex political truth this picture represents. El Chapo was merely an actor operating in a game that remains unchanged by his removal. In fact, “removal” is an ambiguous term since his arrest does not necessarily translate into separating him from his gang. Cardenas Guillen remained the effective head of the Gulf cartel after his arrest and imprisonment in 2003 until his extradition to the United States in 2007. El Chapo’s influence will no doubt continue to be felt while he is incarcerated in Mexico. His extradition to the United States will not occur in the near future, allowing the Sinaloa cartel the time needed to adjust. The cartel is an extremely sophisticated criminal network, and its organizational structure is designed to minimalize the impacts of leader and member losses. Replacements with decades of experience stand ready to assume the necessary roles to ensure the cartels continuance. While there may be some moral victory in El Chapo’s arrest, the actual impact on the drug trade is negligible.

1 The arrest of Arturo Beltran-Leyva in January 2008 triggered an internal gang war in the Sinaloa cartel when the remaining Beltran-Leyva brothers blamed El Chapo for orchestrating the arrest, and in retaliation, the BeLeyva brothers ordered the assassination of one of El Chapo’s sons, 22 year-old Édgar Guzmán on May 9th 2008.

References

Al Jazera. (October 11, 2012). ‘Mexico says Zetas cartel Boss Killed’. Retrieved from: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/americas/2012/10/201210942716300668.html

Bertram, E., & Sharpe, K. (1996/1997). « The Unwinnable Drug War: What Clausewitz Would Tell Us ». World Policy Journal. Vol.13,No. 4, pp. 41-51.

Bugs. (January 12 2011). « El Tomate Reveals the Sinaloa Cartel’s Methods of Operation ». Borderland Beat: Reporting on the Mexican Cartel Drug War. Retrieved from: http://www.borderlandbeat.com/2011/01/el-tomate-reveals-sinaloa-cartels.html

Campos, I. (2011). “In Search of Real Reform: Lessons from Mexico’s Long History of Drug Prohibition”. NACLA Report on the Americas, Vol. 44, No.3, pp. 14-18;37-38. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/893765855?accountid=14789

Friman, R. (2009). ‘Drug Markets and the Selective Use of Violence’. Crime Law Soc Change (52) 285-295.

Molzahn, C., Rios, V., and Shirk, D. (2012). « Drug Violence in Mexico: Data and Analysis Through 2011 ». Trans-Border Institute. Retrieved from: http://justiceinmexico.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/2012-tbi-drugviolence.pdf

Rios, V. (2013). « Why did Mexico become so violent? A self-reinforcing violent equilibrium caused by competition and enforcement ». Trends Organ Crime. Vol. 16, pp.138–155. DOI 10.1007/s12117-012-9175-z

Snyder, R. and Duran-Martinez, A. (2009). “Does Illegality Breed Violence? Drug Trafficking and State-Sponsored Protection Rackets.” Crime Law and Social Change. Vol. 52, No. 3, pp. 253-273.

Laisser un commentaire

Soyez le premier à laisser un commentaire